学习资源

科普文章

免疫检查点抑制剂在SARS-CoV-2感染期间增强T细胞免疫

目前随着各地疫情政策变动,许多肿瘤患者和家属都很关心,新冠对癌症治疗的影响。就此《新型冠状病毒肺炎疫情期间实体肿瘤患者防护和诊治管理相关问题中国专家共识(2022版)》[1]中明确指出对症状消失、无并发症患者在新冠痊愈后重启治疗总体上是安全的,应尽可能恢复符合治疗条件患者的抗肿瘤治疗,必要时根据患者情况进行治疗方案调整,如减量和调整治疗方案,旨在于减少抗肿瘤治疗相关并发症,降低治疗相关脏器不良反应,缩短住院时间和避免非预期住院。在此我们介绍一篇关于PD-1治疗与SARS-CoV-2感染相关性的研究[2],希望对读者有所帮助,也借此机会表达对癌症患者、家属和医护人员的关怀。

Abstract [2]

The COVID-19 pandemic has spread worldwide,yet the role of antiviral T cell immunity during infection and the contribution of immune checkpoints remain unclear. By prospectively following a cohort of 292 patients with melanoma, half of which treated with immune checkpointinhibitors (ICIs), we identified 15 patients with acute or convalescent COVID-19 and investigated their transcriptomic, proteomic, and cellular profiles. We found that ICI treatment was not associated with severe COVID-19 and did not alter the induction of inflammatory and type I interferon responses. In-depth phenotyping demonstrated expansion of CD8 effector memory T cells, enhanced T cell activation, and impaired plasmablast induction in ICI-treated COVID-19 patients. The evaluation of specific adaptive immunity in convalescent patients showed higher spike (S), nucleoprotein (N), and membrane (M) antigen-specific T cell responses and similar induction of spike-specific antibody responses. Our findings provide evidence that ICI during COVID-19 enhanced T cell immunity without exacerbating inflammation.

摘要[2]

COVID-19 大流行已在全球蔓延,但抗病毒 T 细胞免疫在感染过程中的作用和免疫检查点的作用仍不清楚。通过前瞻性跟踪 292 名黑色素瘤患者(其中一半接受免疫检查点抑制剂 (ICI) 治疗),我们确定了 15 名急性或恢复期 COVID-19 患者,并研究了他们的转录组学、蛋白质组学和细胞学特征。 我们发现 ICI 治疗与COVID-19 重症无相关性,也没有改变炎症和 I 型干扰素反应的诱导。深入的表型分析表明,较之对照组,在接受ICI 治疗的 COVID-19 患者中,观察到CD8 效应记忆 T 细胞扩增,T 细胞活性增强和浆母细胞诱导受损。对恢复期患者特异性适应性免疫的评估显示出更高的针对SARS-CoV-2病毒尖峰 (S)、核蛋白 (N) 和膜 (M) 抗原特异性 T 细胞反应以及类似的针对尖峰(S)的特异性抗体反应诱导。我们的研究结果提供的证据表明,在COVID-19 期间进行 ICI 可增强 T 细胞免疫力,而不会加剧炎症。

严重急性呼吸综合征2型冠状病毒(SARS-CoV-2)于2019年12月出现,并在全球范围内传播,导致冠状病毒病2019 (COVID-19)大流行,引起约5%的重症,1%的致死率[3, 4]。COVID-19对癌症患者的影响以及不同癌症治疗方案对COVID-19严重程度的影响仍在调查中。早期研究表明,癌症患者的COVID-19疾病严重程度和病死率更高(达到28%),很可能是癌症治疗引起的免疫抑制和合并症增加所导致的[5, 6];然而,后续的回顾性和前瞻性研究表示癌症并未导致COVID-19更高的死亡率[7-10]。这些不一致的结果可能是由于患者群体的癌症类型、分期和治疗方案等诸多因素的异质性造成的。

COVID-19的重症是由于人体对感染的过度的炎症反应造成的,导致肺组织损伤、急性呼吸窘迫综合征,甚至呼吸衰竭和死亡。这种过度炎症可能导致细胞免疫的衰竭,例如T细胞和NK细胞的衰竭标志物PD-1和TIM-3的上调[11, 12]。另有研究表明,大多数重症COVID-19患者表现为T细胞凋亡过多和衰竭标志物上调导致的淋巴细胞减少[13]。并且也有研究显示,在疾病恢复前几天,以及在病后恢复期,都观察到了SARS - CoV -2特异性的CD38+ HLA-DR+ CD8+和CD4+ T衰竭状态细胞[14-16]。基于这些观察,至少有三项临床试验正在评估PD-1抑制剂治疗COVID-19的效果 (NCT04356508、NCT04333914和NCT04268537)。然而,最近的分析报告了关于接受PD-1治疗的肺癌患者有更高COVID-19重症风险的相互矛盾的结果,这可能归因于两者共同的诱发风险因素,如吸烟史或者年龄等[17-19]。因此,免疫检查点抑制剂(ICIs)是通过激发抗病毒适应性免疫反应发挥有益作用,还是通过导致过度炎症反应导致器官损伤和衰竭而发挥有害作用,这仍然是一个悬而未决的问题[20]。

在本研究中,作者描述了COVID-19的临床表达,并监测了III期和IV期黑色素瘤患者体内抗SARS - CoV -2抗体的演变过程。他们发现ICI治疗与COVID-19重症无相关性,也不加剧炎症,反而证明它增加了抗SARS - CoV -2的特异性T细胞免疫力。这些初步结果与其他结果[18, 21]一致,支持在COVID-19流行期间继续使用PD-1阻断剂的安全性。

有研究表明,急性SARS-CoV-2感染导致T细胞功能迅速缺失,而特异性CD8+ T细胞对于抗病毒感染有重要作用[22, 23]。在本研究中,作者发现在SARS-CoV-2感染活跃期,接受ICI治疗的患者诱导了更高比例的CD8+ 效应记忆T细胞,并且这一差异在恢复期中持续存在。虽然他们无法评估这些T细胞群的特异性,但他们发现ICI治疗的患者对SARS-CoV-2多肽的反应增强,支持检查点抑制增强CD8+ T细胞对SARS-CoV-2免疫的假设。

有趣的是,最近的研究报告显示,尽管SARS-CoV-2特异性记忆CD8+T细胞可检测并持续存在,但其频率比甲型流感病毒或EB病毒感染时低10倍[24]。作者认为SARS-CoV-2感染限制了效应记忆和中心记忆T细胞亚群的克隆扩增和分化,并影响了临床重症程度和未来再次感染的风险。我们的数据提供了实验证据,表明用抗PD-1药物治疗可以恢复这种缺陷,并表明SARS-CoV-2感染部分通过耗竭标记物的上调限制了T细胞的扩张和分化。

总之,我们的数据与其他数据[18][21]一致,支持在COVID-19大流行期间使用抗PD-1药物治疗对黑色素瘤癌症患者不构成更高风险的说法。当然本研究有其局限性(病人人数少,仅限于黑色素瘤),作者仍建议每次就诊前应仔细评估获益和风险平衡,包括个体风险因素,并进行后续治疗选择,这与其他专家指导建议是一致的[25]。此外,免疫学分析表明,ICIs不会加剧炎症,并可能有助于在急性感染的情况下加速和放大抗病毒T细胞免疫,以及建立长期免疫。这一假设值得进一步评估,如果得到验证,可能对旨在治疗病毒感染或提高疫苗接种效果的策略具有重要意义[26, 27]。

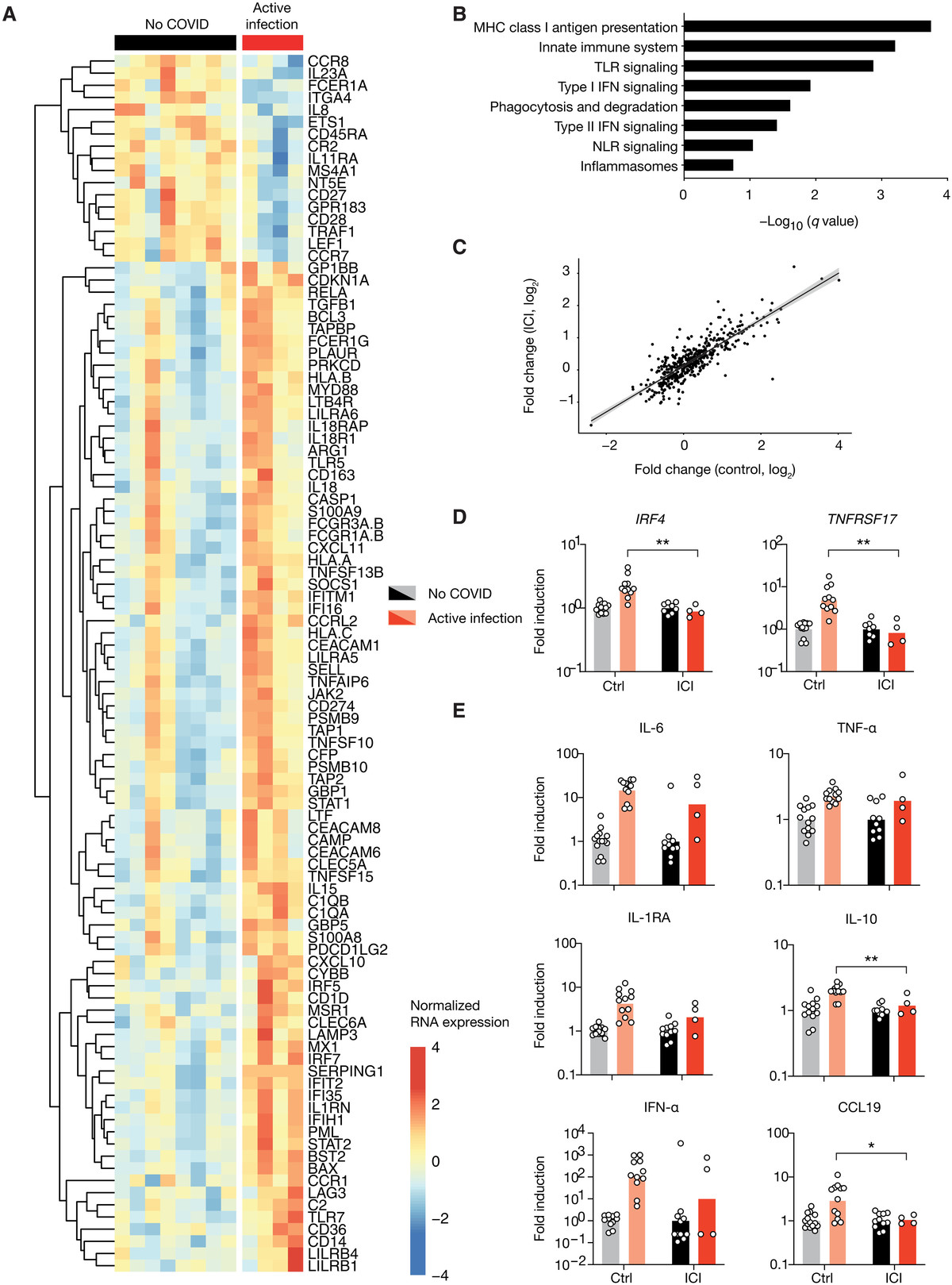

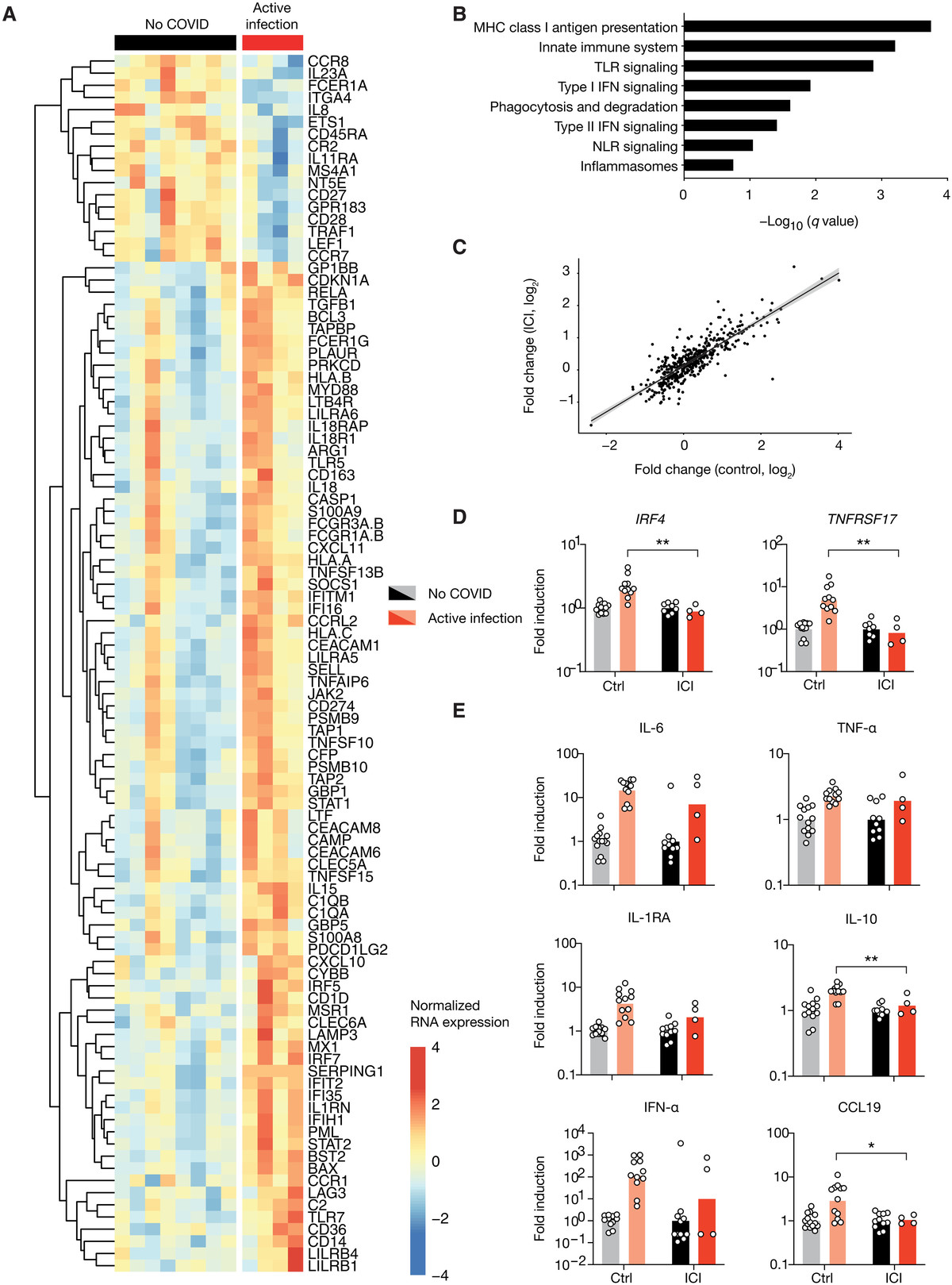

图1 使用检查点抑制剂治疗的患者在COVID-19活跃期表现出典型的转录组和蛋白质组炎症反应

(A至C)来自一组非黑色素瘤患者和一组接受PD-1治疗患者的COVID-19活跃期患者和健康对照的全血转录组谱。(A)抗PD-1治疗队列中covid -19感染患者和未感染患者之间100个差异最大的基因热图。(B) PD-1治疗队列中COVID-19活跃期富集通路的GSEA。(C)每个队列中COVID-19患者与未感染患者之间RNA表达倍数的变化。每个点代表一个基因。(D)来自两个队列患者的RNA表达数据,每个队列归一化为未感染组的平均值。(E)两组患者的蛋白质组数据,归一化如(D)所示。每个点对应一个患者,柱状图代表平均值。使用未配对t检验确定显著性。*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01。MHC,主要组织相容性复合体;TLR, toll样受体;NLR, nod样受体。

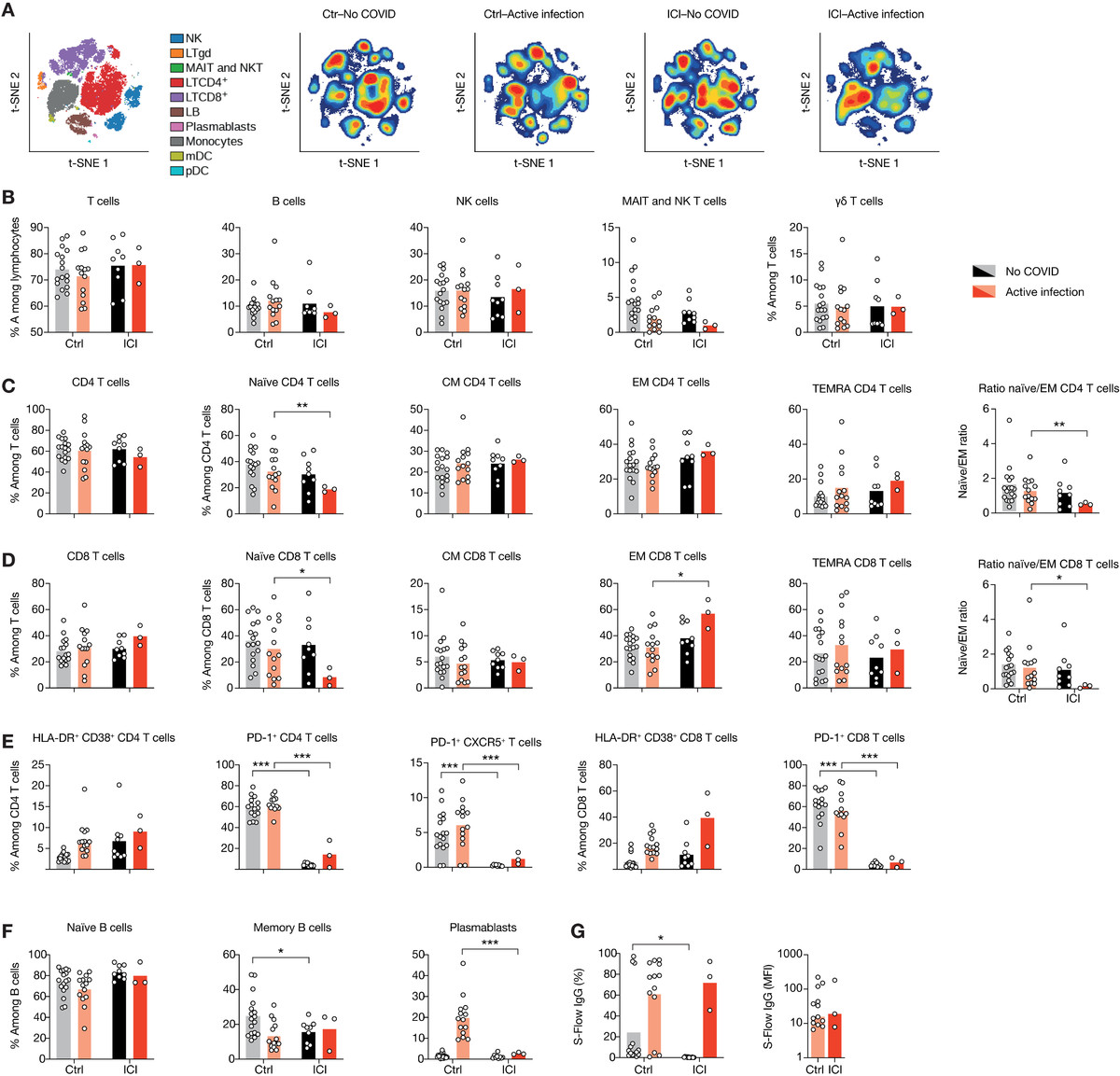

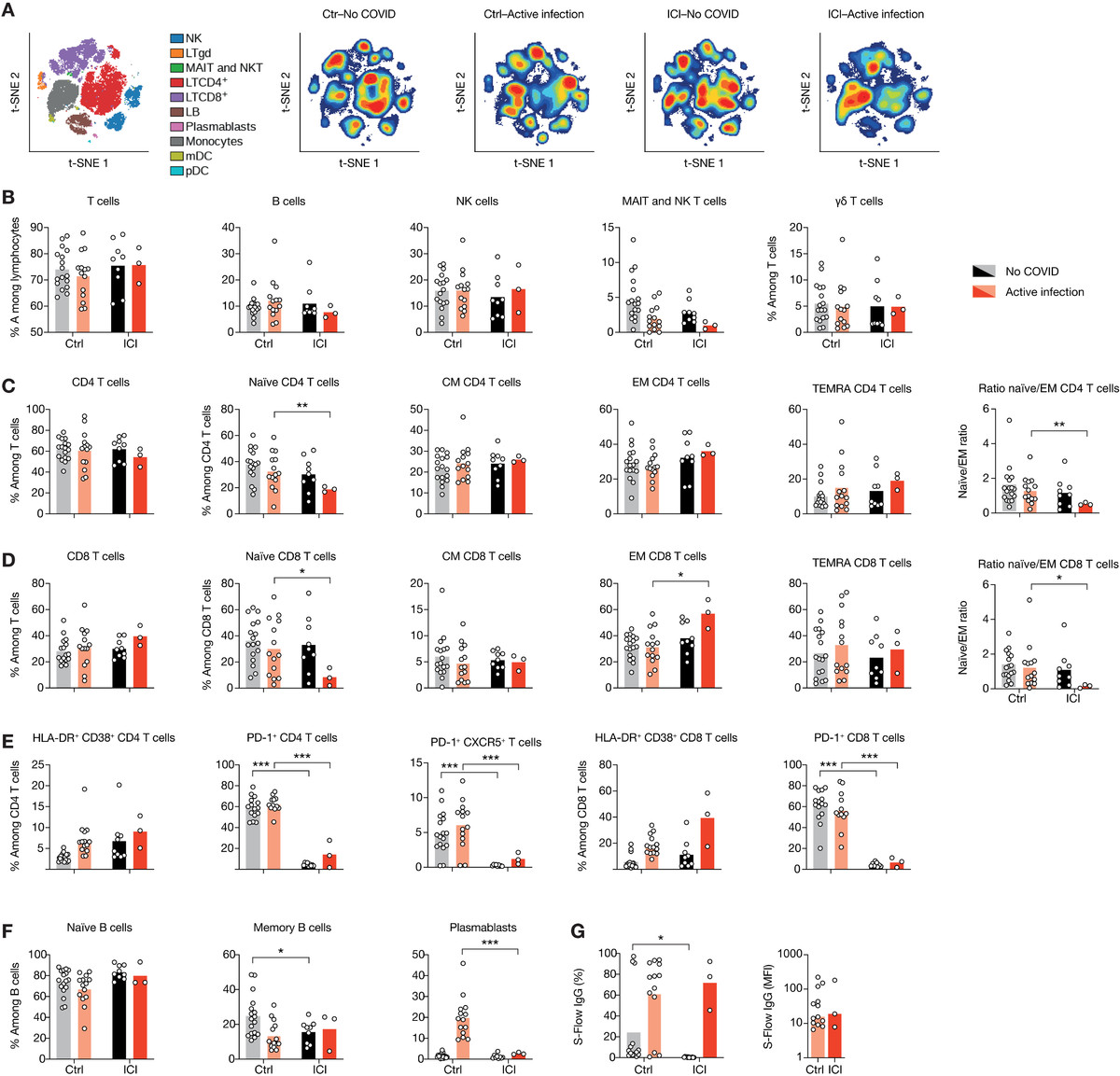

图2 接受ICI治疗的患者显示T细胞活化谱升高

(A)去除粒细胞后的血白细胞viSNE图,用30个标记物染色,用海量细胞仪测量。细胞根据它们表达的标记的组合(左)自动分离成空间上不同的子集。LTγδ, γδ T淋巴细胞;MAIT,粘膜相关不变T细胞;LB、B淋巴细胞;NK,自然杀伤细胞。然后根据两组感染和未感染患者的细胞密度对viSNE图进行着色。红色表示细胞密度最高,蓝色表示细胞密度最低。(B)外周血淋巴细胞中CD3+ T细胞、CD19+ B细胞、CD3−CD56+ NK细胞、MAIT细胞的比例。(C和D) T细胞亚群的比例。(E)根据活化(CD38和HLA-DR)、衰竭(PD-1)和Tfh标记(CXCR5+PD-1+)的表达分析特定T细胞亚群的功能状态。(F) B细胞亚群比例。(G)用S- flow法定量SARS-CoV-2 spike (S)特异性IgG抗体。左:表达S蛋白的细胞百分比。右:归一化平均荧光强度(MFI)每个点对应一个病人,条形图代表平均值。采用未配对t检验,然后进行多重检验的Holm-Sidak校正来确定显著性。*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001。

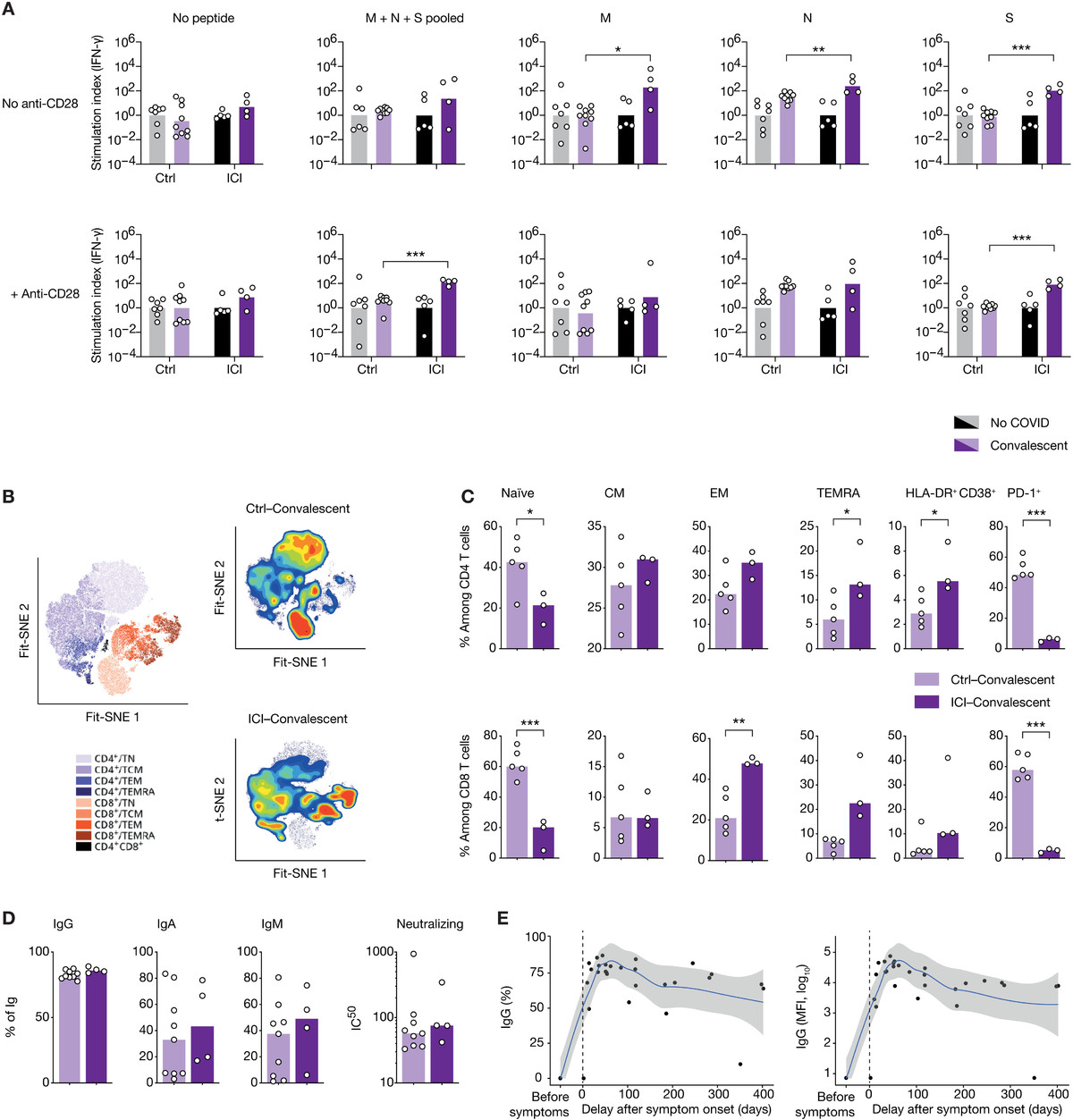

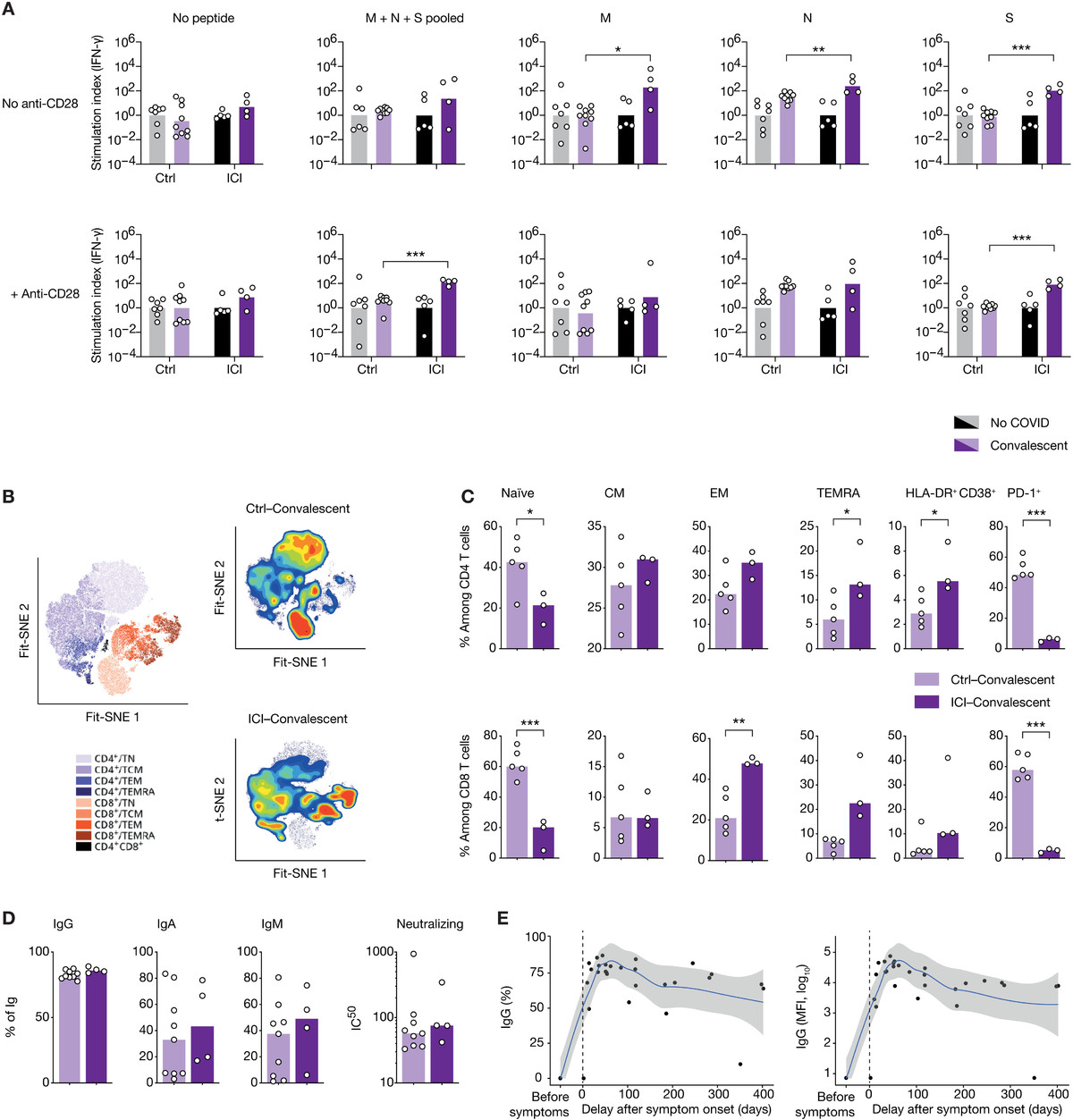

图3 ICI治疗对SARS-CoV-2抗病毒细胞免疫具有持久影响。

(A)采集COVID-19恢复期患者全血,用刺突蛋白(S)、核蛋白(NP)或膜蛋白(M)肽池刺激48小时,然后收集上清,采用数字ELISA法检测IFN-γ。刺激指数由每个队列的未感染组归一化的IFN-γ浓度组成。(B)恢复期患者淋巴细胞的Fit-SNE图,用海量细胞仪测量,图按细胞密度着色。红色表示细胞密度最高,蓝色表示细胞密度最低。(C)两组恢复期患者T细胞亚群的比例。(D)每种Ig亚型SARS-CoV-2 s特异性IgG+、IgA+或IgM+细胞的频率。(E) ICI治疗患者SARS-CoV-2 s特异性IgG+的寿命,以百分比或MFI表示。每个点对应一个样本(n = 33),柱状表示平均值。采用局部估计散点平滑法得到非参数回归曲线。使用未配对t检验确定显著性。*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001。IC50,中值抑制浓度。

本文仅作信息分享,不代表礼进生物公司立场和观点,也不作治疗方案推荐和介绍。如有需求,请咨询和联系正规医疗机构。

参考文献

1. [Chinseexpert consensus on issues related to the protection, treatment and management

of patients with solid tumors during COVID-19 (2022 edition)]. ZhonghuaZhong Liu Za Zhi, 2022. 44(10): p.1083-1090.2. Yatim, N., etal., Immune checkpoint inhibitorsincrease T cell immunity during SARS-CoV-2 infection. Science Advances,2021. 7(34): p. eabg4081.

3. Salje, H., etal., Estimating the burden of SARS-CoV-2in France. Science, 2020. 369(6500):p. 208-211.

4. Huang, C., etal., Clinical features of patientsinfected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet, 2020. 395(10223): p. 497-506.

5. Mehta, V., etal., Case Fatality Rate of CancerPatients with COVID-19 in a New York Hospital System. Cancer Discov, 2020. 10(7): p. 935-941.

6. Dai, M., et al., Patients with Cancer Appear More Vulnerableto SARS-CoV-2: A Multicenter Study during the COVID-19 Outbreak. CancerDiscov, 2020. 10(6): p. 783-791.

7. Lee, L.Y.W., etal., COVID-19 prevalence and mortality inpatients with cancer and the effect of primary tumour subtype and patient

demographics: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol, 2020. 21(10): p. 1309-1316.8. Basse, C., etal., Characteristics and Outcome ofSARS-CoV-2 Infection in Cancer Patients. JNCI Cancer Spectr, 2021. 5(1): p. pkaa090.

9. Lee, L.Y., etal., COVID-19 mortality in patients withcancer on chemotherapy or other anticancer treatments: a prospective cohort

study. Lancet, 2020. 395(10241):p. 1919-1926.10. Miyashita, H., etal., Do patients with cancer have apoorer prognosis of COVID-19? An experience in New York City. Ann Oncol,2020. 31(8): p. 1088-1089.

11. Hotchkiss, R.S.,et al., Immune checkpoint inhibition insepsis: a Phase 1b randomized study to evaluate the safety, tolerability,

pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of nivolumab. Intensive Care Med,2019. 45(10): p. 1360-1371.12. Delano, M.J. andP.A. Ward, Sepsis-induced immunedysfunction: can immune therapies reduce mortality? J Clin Invest, 2016. 126(1): p. 23-31.

13. Zheng, H.Y., etal., Elevated exhaustion levels andreduced functional diversity of T cells in peripheral blood may predict severe

progression in COVID-19 patients. Cell Mol Immunol, 2020. 17(5): p. 541-543.14. Grifoni, A., etal., Targets of T Cell Responses toSARS-CoV-2 Coronavirus in Humans with COVID-19 Disease and Unexposed

Individuals. Cell, 2020. 181(7):p. 1489-1501.e15.15. Mathew, D., etal., Deep immune profiling of COVID-19patients reveals distinct immunotypes with therapeutic implications.Science, 2020. 369(6508).

16. Weiskopf, D., etal., Phenotype and kinetics ofSARS-CoV-2-specific T cells in COVID-19 patients with acute respiratory

distress syndrome. Sci Immunol, 2020. 5(48).17. Tagliamento, M.,et al., Italian survey on managing immunecheckpoint inhibitors in oncology during COVID-19 outbreak. Eur J ClinInvest, 2020. 50(9): p. e13315.

18. Luo, J., et al., Impact of PD-1 Blockade on Severity ofCOVID-19 in Patients with Lung Cancers. Cancer Discov, 2020. 10(8): p. 1121-1128.

19. Robilotti, E.V.,et al., Determinants of COVID-19 diseaseseverity in patients with cancer. Nat Med, 2020. 26(8): p. 1218-1223.

20. Pickles, O.J., etal., Immune checkpoint blockade:releasing the breaks or a protective barrier to COVID-19 severe acute

respiratory syndrome? Br J Cancer, 2020. 123(5): p. 691-693.21. Trojaniello, C.,M.G. Vitale, and P.A. Ascierto, Checkpointinhibitor therapy for skin cancer may be safe in patients with asymptomatic

COVID-19. Ann Oncol, 2021. 32(5):p. 674-676.22. Zhou, R., et al., Acute SARS-CoV-2 Infection Impairs DendriticCell and T Cell Responses. Immunity, 2020. 53(4): p. 864-877.e5.

23. Peng, Y., et al., Broad and strong memory CD4(+) and CD8(+) Tcells induced by SARS-CoV-2 in UK convalescent individuals following COVID-19.Nat Immunol, 2020. 21(11): p.1336-1345.

24. Habel, J.R., etal., Suboptimal SARS-CoV-2-specificCD8(+) T cell response associated with the prominent HLA-A*02:01 phenotype.Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2020. 117(39):p. 24384-24391.

25. 北京大学肿瘤医院新型冠状病毒疫情防控领导小组 and 加. 季, [Not Available]. BeijingDa Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2020 Apr 18;52(2):199-203. doi:

10.19723/j.issn.1671-167X.2020.02.001.26. Waissengrin, B.,et al., Short-term safety of the BNT162b2mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in patients with cancer treated with immune checkpoint

inhibitors. Lancet Oncol, 2021. 22(5):p. 581-583.27. Wong, H.S., etal., Transcriptome network analyses inhuman coronavirus infections suggest a rational use of immunomodulatory drugs

for COVID-19 therapy. Genomics, 2021. 113(2):p. 564-575.

沪公网安备 31011502015333号

沪公网安备 31011502015333号